During our TDD Dojo session on July 23, 2021, I have demonstrated the benefits of writing one test at a time before writing any implementation code. The demo was recorded and published on our WSBC Technical Blog (Sensei Alex "fakes it until he makes it" in our Test-driven Development (TDD) dojo).

Due to the time limitation, I didn’t get a chance to demonstrate another benefit of writing one test at a time and doing mutation testing – the ability to keep the entire suite of tests lean. This episode takes a closer look into the importance of preventing the test suite from becoming bloated.

Tests are non-productive

No one hired us to write tests. We write them because that is the best way to speed up the delivery. Still, we need to keep in mind that tests are not a product we could sell. No customer would ever agree to pay someone to write tests; customers are only interested in paying for the finished product.

Another downside of tests (besides being expensive to write) is that tests consume the time to run. Tests also consume the time needed for the maintenance. As such, we view tests as a liability.

With that in mind, we should cultivate the attitude that tests are a necessary evil, and therefore must be kept at a bare minimum. Kent Beck famously wrote:

"I get paid for code that works, not for tests, so my philosophy is to test as little as possible to reach a given level of confidence."

The challenge now becomes how do we make sure we only produce minimum number of tests while retaining high level of confidence in our tests? Proliferation of tests is highly undesirable, but how do we know when to stop adding more tests?

The question also pertains to knowing how to get rid of the tests that are already written but serve no purpose? Let’s investigate some code examples to illustrate how to keep the proliferation of unnecessary tests at bay.

Tests help grow the quality design

One of the main reasons we are doing Test-Driven Development (TDD) is due to the demonstrable ability of that method to guide us in producing quality design. For example, how did the design of the Tip Calculator (as presented in our TDD Dojo hands-on session that was published in the above WSBC Technical Blog) grow from following the TDD method?

The first step we did when designing the Tip Calculator is to stop and think about the simplest expectation: we’d like our automated service to recognize that there is such thing as ‘Terrible’ rating. Once we have formulated that expectation, we rolled up our sleeves and wrote our first test:

[Fact]

public void TerribleRatingIsValid()

{

var expectedResponseForTerribleRating = true;

var actualResponseForTerribleRating = tipCalc.IsRatingValid("Terrible");

Assert.Equal(expectedResponseForTerribleRating, actualResponseForTerribleRating);

}

The test TerribleRatingIsValid describes the expectation that when we give the string “Terrible” to our application, asking it if that rating is valid, it will respond with true. That means that we must teach our application to be able to look for the ratings stored somewhere on the system and tell us either that it found the rating we asked it to look for (by returning true), or that is couldn’t find it (by returning false).

After we’ve implemented that capability, we turned our attention to the next expectation. We are expecting our app to be able to tell us the percentage tip for the “Terrible” rating, and that percentage tip is expected to be 0%. We then created a new test (TerribleRatingIs0Tip) in which we ask the Tip Calculator to tell us what the tip for the rating “Terrible” is. If the app returns 0, the test will pass, otherwise the test fails:

[Fact]

public void TerribleRatingIs0Tip()

{

var expectedTipForTerribleRating = 0;

var actualTipForTerribleRating = tipCalc.TipForRating("Terrible");

Assert.Equal(expectedTipForTerribleRating, actualTipForTerribleRating);

}

The last thing we did to fulfill the scenario 1 specified in the Tip Calculator user story was to create the expectation that the app will correctly calculate the grand total if given the bill total and the service rating. We created the test TerribleRatingFor100Is100, in which we stated that if the bill total is $100.00 and the rating is “Terrible”, the calculated grand total should be $100.00 (meaning, no tip, or more precisely, 0% tip):

[Fact]

public void TerribleRatingFor100Is100()

{

var expectedTotalForTerribleRatingFor100 = 100.00;

var actualTotalForTerribleRatingFor100 = tipCalc.CalculateGrandTotal(100.00, "Terrible");

Assert.Equal(expectedTotalForTerribleRatingFor100, actualTotalForTerribleRatingFor100);

}

Now that we got scenario 1 implemented, we moved to scenario 2 – calculate grand total for $100.00 bill total and “Poor” service rating. The stated expectation is that in such scenario the grand total should be $105.00, which means that “Poor” rating is calculated with the 5% tip.

In designing the processing of the “Poor” rating we followed the same design that guided us in designing the “Terrible” rating. We now proceeded to design the “Poor” rating by crafting three tests:

1) Check if “Poor” rating is valid

[Fact]

public void PoorRatingIsValid()

{

var expectedResponseForPoorRating = true;

var actualResponseForPoorRating = tipCalc.IsRatingValid("Poor");

Assert.Equal(expectedResponseForPoorRating, actualResponseForPoorRating);

}

2) Check if “Poor” rating is calculated with 5% tip

[Fact]

public void PoorRatingIs5Tip()

{

var expectedTipForPoorRating = 5;

var actualTipForPoorRating = tipCalc.TipForRating("Poor");

Assert.Equal(expectedTipForPoorRating, actualTipForPoorRating);

}

3) Check if grand total for the bill total $100.00 and rating “Poor” is $105.00

[Fact]

public void PoorRatingFor100Is105()

{

var expectedTotalForPoorRatingFor100 = 105.00;

var actualTotalForPoorRatingFor100 = tipCalc.CalculateGrandTotal(100.00, "Poor");

Assert.Equal(expectedTotalForPoorRatingFor100, actualTotalForPoorRatingFor100);

}

We’ve also completed the app by implementing similar designs for the “Good”, “Great” and “Excellent” service rating. But for the purposes of this discussion, we’ll limit the analysis to only two ratings: “Terrible” and “Poor”.

All tests pass, no mutants survive

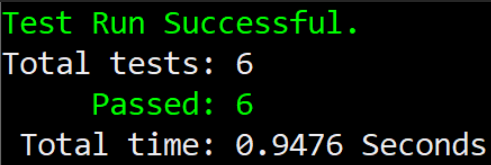

When we run tests, they are all in green!

We feel good knowing that our design is delivering as expected. However, prudent engineering demands that we examine our design more thoroughly, so we will now run mutation testing:

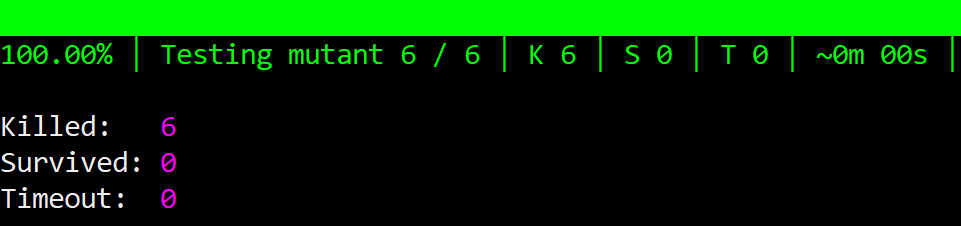

Mutation testing tool created 6 mutants and none of those mutants survived. Our design is indeed airtight!

Do we have bloated tests?

And now for the punchline: just because we have a solution where all tests are passing and no mutants survived, it does not mean that our solution is not bloated. We may have some redundant tests, which is never good. Redundant tests are slowing the test suite runtime, and they’re also adding unwanted noise to our code. Every line of code (including tests) must be maintained, and that maintenance requires spending extra cycles. Such potential waste reduces our precious bandwidth and is to be avoided.

So, how do we check for bloated tests?

We must perform some housekeeping duties. Thanks to the mutation testing tool, the chore will most likely be very light. What is advisable to do now that we have an airtight solution is to try and get rid of some tests. We must go one test at a time. Let’s first eliminate the first test (TerribleRatingIsValid) and pay attention to see if mutation testing discovers any surviving mutants. After running mutation testing without having the first test, we see that our solution still has killed all mutants! Great news. Let’s carry on by removing the second test (TerribleRatingIs0Tip). After running mutation testing again, we see that no mutants survive. Yay!

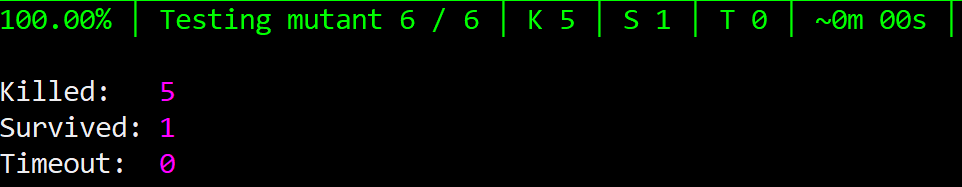

Let’s try removing the third test (TerribleRatingFor100Is100). Run mutation testing again and – uh-oh! – one mutant survives!

That test was essential, so we’d better reinstate it quickly.

Moving along, we can now try to remove the fourth test (PoorRatingIsValid). Running mutation testing after removing that test kills all mutants. Good show. Now try to remove the fifth test (PoorRatingIs5Tip). After removing this test and running mutation testing, we see that still all mutants get killed.

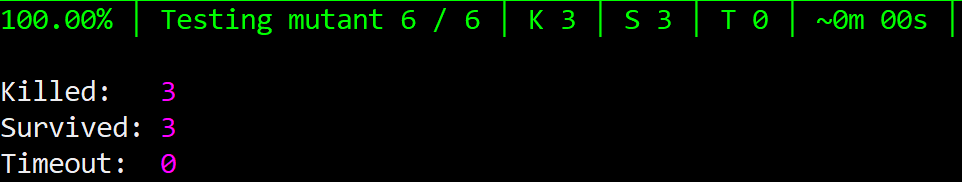

Finally, we try to remove the last test – PoorRatingFor100Is105. After running mutation testing, we get startled: 3 mutants survived!

Oh-oh, quickly restore that last test, and we’re back to normal.

Analysis

In the above simple exercise, we have delivered a solid design guided by 6 micro tests. When we got all 6 tests to pass, we ran mutation testing and got additional confidence boost when no mutants have survived. We were assured that our solution is now placed on solid ground.

However, just because we have a complete and solid solution doesn’t mean it is engineered properly. We demonstrated the shoddy engineering by removing some tests and seeing that despite the tests not being present, no mutants survived the execution of the mutation testing.

In the end, we reached the point when we realized that only 2 tests are needed to assure highest possible quality of the solution. By eliminating 4 tests out of the total of 6 tests, we have achieved two thirds reduction of the test bloat. Major accomplishment (it always feels great when we manage to get rid of some deadwood code!)

Discussion

How can we be sure that by removing a test (or several tests), we're not tossing the proverbial baby out with the dirty bathwater? I often hear that question being asked when we start getting rid of those redundant tests.

We can be sure that we haven't discarded valuable tests by the virtue of the fact that removing a test did not produce a surviving mutant (or, surviving mutants). For example, we may think that TerribleRatingIsValid test is offering a unique value. However, if indeed that test were unique, removing it would out of necessity produce at least one surviving mutant. Same reasoning applies to the dilemma we may experience when asked to remove TerribleRatingIs0Tip test. But even after removing that test we see that no mutants survived. That means that whatever these two tests are testing, has already been tested by the third test: TerribleRatingFor100Is100.

If we now know that TerribleRatingFor100Is100 test is checking both that "Terrible" rating is valid and also that "Terrible" rating has 0% tip, we should be able to understand why are TerribleRatingIsValid and TerribleRatingIs0Tip tests completely unnecessary. Those tests are just clutter, only adding noise and providing no value to our solution.

Same discussion then apples for the "Poor" rating processing. PoorRatingIsValid and PoorRatingIs5Tip tests are redundant because all the testing these two tests are performing is already performed by the PoorRatingFor100Is105 test. It is therefore safe to reduce the number of tests from 6 down to only 2.

Conclusion

We have seen in the above demonstration how, while writing micro tests before writing implementation code is an indispensable technique for producing solid, decoupled design, the final product oftentimes will end up not needing some of those micro tests. We can view those redundant tests as scaffolding, something we erect for the time being, while we are working on the product. But eventually the time comes when all that scaffolding isn’t needed anymore, and it is advisable to remove it. Removing the scaffolding (i.e., redundant tests) not only minimizes the noise and maximizes the signal, but also relieves the system from the burden of having to run unnecessary tests each time test suite executes.