Continuous learning is the essential prerequisite for staying competitive in the market. The competitive edge is oftentimes won by innovating. At WorkSafeBC, we take continuous education very seriously. On top of our regular training sessions, coding Dojos, ad hoc coding bootcamps, weekly micro learning episodes, regular blog posts on WorkSafeBC Technical Blog, etc., we also deliver regular Lunch & Learn sessions. Last month, Christine Ozeroff (our Manager of Innovation & Technology Learning) organized an experimental Lunch & Learn session to teach Test Driven Development (TDD) to non-technical staff. It was a daring experiment (we don’t know of anyone else ever attempting to do something like that), and the stakes were high – will the session prove to be useful, or will we merely manage to confuse the attendees?

We’re happy to report that the outcome of the session exceeded our expectations. Participants were pulled into the presentation and encouraged to interrupt the proceedings by asking very valuable and useful questions. At the end of the session, the overall sense was that the group learned something valuable.

How it all began

About two years ago the DevOps department introduced the practice of Test Driven Development (TDD). We started with training sessions then moved into regular TDD Dojos with kata exams. Today, all developers have reached at least the TDD yellow belt level, some are already at the orange belt level and moving on to take the green belt katas.

That success created a bit of a stir as other departments began hearing the term TDD being thrown around. The curiosity started rising, so the time was opportune to consider having a session that would introduce and demystify the TDD practice.

How we went about organizing the session

Alex Bunardzic proposed to deliver a hands-on exercise that would illustrate the TDD practice to staff that never performed any computer programming. Naturally, the hands-on exercise would not be in any way related to solving a computer programming challenge (because that would be counter-productive). After giving it some thought, Alex decided to use the familiar process of writing a short story. Everyone has at one point in their schooling written a short story or a short essay. The challenge now became: how do we write a short story/essay using the TDD approach?

To enable the actual hands-on exercise, Alex had to quickly innovate and create, from scratch, a testing framework that would enable writers to first express an expectation before actually putting the pen on paper (or, in this case, before starting to type the content of their short story).

The session was conducted using Alex’s newfangled testing framework. We were a bit concerned whether this experimental approach would make any sense to non-programmers, but as the session began unfolding, our anxieties were quickly appeased.

How did the session unfold?

Unfortunately, on the day we held the session Christine was out of the office; in her place, we had Chloe Ernst act as the MC. Chloe did a fantastic job setting up the stage, breaking the ice and explaining to the staff in attendance what the session is all about and what to expect.

Once Chloe handed the control over to Alex, attendees were treated to a brief introduction to TDD, as it is practiced in software development. Shortly after the presentation began the questions started to come in. The frequency of interesting questions increased as the session moved to the hands-on exercise. Alex took the time to address each question to the best of his ability. What was noteworthy was that the questions, coming from non-programmers, were very insightful and went straight into the very essence of the test-first approach to developing anything (be it a short story, a computer program/app, or anything else).

At the end of the session, most of the questions were addressed and the feeling was the attendees left the presentation with a better understanding of the value that TDD practices bring to the quality of delivery.

Some interesting interactions with the participants

Let’s investigate some interesting details that unfolded during the hands-on session. Alex set the stage for the hands-on demonstration by explaining that we always start our work by formulating expectations. In the case of writing a short story, the first expectation is that the story should have a title. The test-driven approach requires automatic verifications that confirm whether our expectations have been met. Alex demonstrated the framework he built specifically to write textual documents (please see the Appendix for more on this framework). The only way a system will automatically verify if the exceptions are met or not met is if we provide and prescribe formal rules to follow.

In this case, we are working with a system that has two moving parts: one moving part is the story document (where by ‘moving’ we mean the content of the document keeps changing), the other moving part is a separate document that contains formalized expectations (we call that document 'tests').

Because the rule of the test-driven development game is that we must always specify expectations before we make changes to the content, the first thing we do is declare the expectation that the short story document must contain a title.

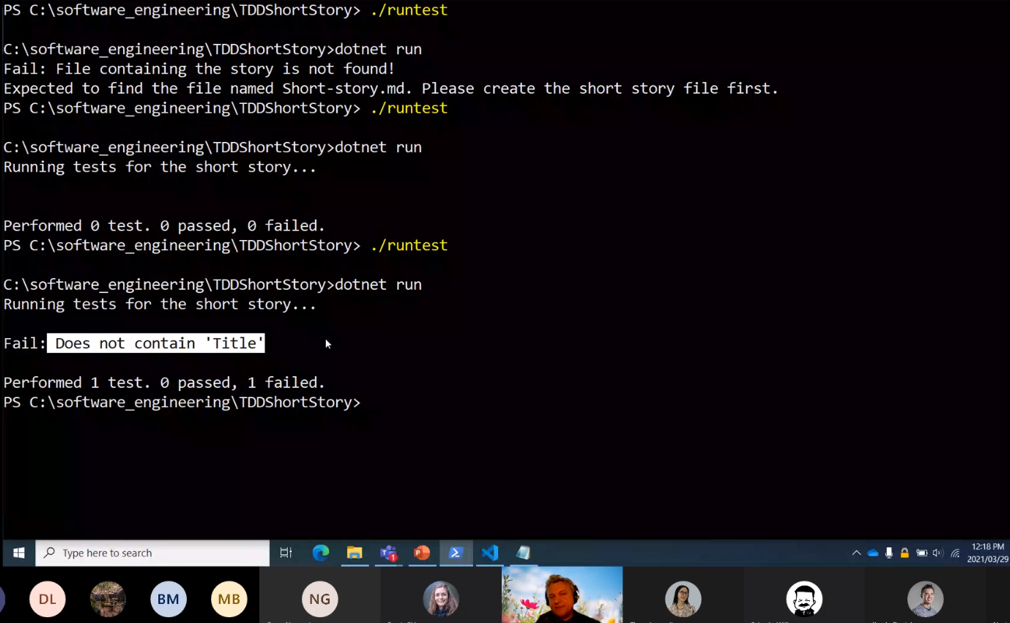

When we run the testing framework we see that it finds our story writing system in a broken state. To begin with, the testing framework was expecting to find a short story document and failed. Once we created the expected document, the testing framework checked to see if the short story contains the title. It could not find the title, so it failed.

From that moment on, the hands-on session continued to alternate between adding the expectation, seeing it fail, and then making changes to the document to fulfill the failed expectation. Rinse, repeat, until we get to the point where we feel that the first draft of the short story is ready for review.

Few questions emerged during the session:

Sangeeta Ben asked, “Is the testing framework case sensitive?” Alex answered by making the change to one of the tests by replacing the word starting with the upper-case with the same lower-case letter, saved the change and re-ran the tests. The test failed, which gives a clear answer that the tests are case sensitive.

Boris Nester asked: “What happens when we learn that there is a new compliance regulation that implies that the business policy rule has changed? Do we then write a new test?” Alex attempted to answer by changing one of the existing tests and re-running all tests. The changed test failed because the implemented document did not meet the new expectations. The important takeaway point from this example is that change to the system must never be implemented at the document level. It must always be first made to the specification (i.e. the tests that declare the expectations). Once the change to the tests has been made, we need to run the tests to see that the implementation is causing one or more tests to fail. We then go back and make modifications to the implementation (i.e. we refactor) until the modified expectations to the test cease to cause the tests to fail.

Steven Tate asked: “Who writes the tests? I’m assuming it’s the creators of the content, in the case of software development it’s the developers. Is that correct?” Alex answered: “Not necessarily. There may be a new business policy rule that people who are developing software may not know about. Tests could be written by the team comprising not only developers but also other subject matter experts.”

Attendee’s feedback

Attendees provided their insight on their experience and what they learned during this Lunch and Learn session. Alex’s efforts to make this session an engaging and relaxed environment for everyone to ask questions came through, as several comments reflected on how attendees like Sangeeta Ben “felt comfortable attending...knowing the session was for non-techies”.

Pindy wrote “Alex made it easy to understand that TDD helps with producing simple designs…, and clean and meaningful code”.

Boris Nester sums his insights of TDD as it’s “all about shortening the feedback loop to enable quicker product evolution while maintaining quality and not impacting other parts of the application”.

Thank-you to everyone for making this session a success!

Appendix

Necessity is the mother of invention, and once Christine and Alex agreed that teaching TDD by doing the hands-on demo on how to write a short story would be a good approach, the work on creating a testing framework began. Alex decided to build a simple, no bells-and-whistles framework.

The short story testing framework is based on a couple of simple assumptions: there will be a document located on the local disk and that document will have a name and an md extension (md for markdown language). In addition to that there will be another document called tests.txt.

Each time the tests run, the framework will attempt to locate and open the .md file. If it fails, it will report an error in the console. If it finds and opens the document, it will read it line-by-line to see if the content in the document satisfies the expectations declared in the tests.txt.

The testing framework is expecting several syntactical formulations that start at each non-blank line in the tests.txt file. For example, one formalized rule is Must contain:. This rule grabs the specified content to the right of the Must contain: statement and then tries to find that content in the .md document. The simplest implementation of that rule would be:

Must contain: Title

Any content could be specified to the right of the Must contain: rule. The testing framework will examine the short story document to see if the specified expectation has been met.

It is also possible to specify the expectation that the short story document must consist of a certain structure. That expectation can be encoded in the test.txt by using the Minimum number of subtitles: formalized expectation.

Of course, the testing framework can check for minimum number of words, maximum number of words, minimum number of paragraphs, maximum number of paragraphs, minimum length in characters, maximum lenght, and so on.

Using this primitive testing framework, it is possible to specify a lot of expecations that are then driving the story writing process.