Indeed, the ratio of time spent reading vs. writing is well over 10:1… Because this ratio is so high, we want the reading of code to be easy, even if it makes the writing harder. — Robert C. Martin, Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship

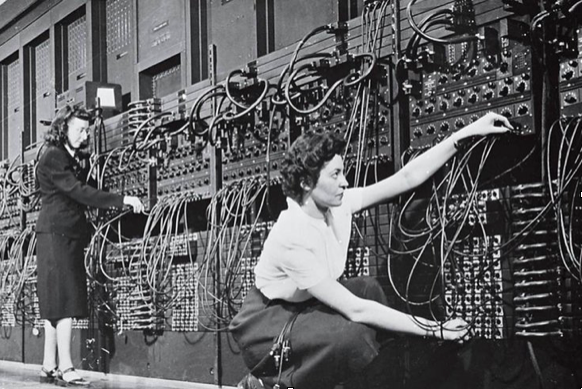

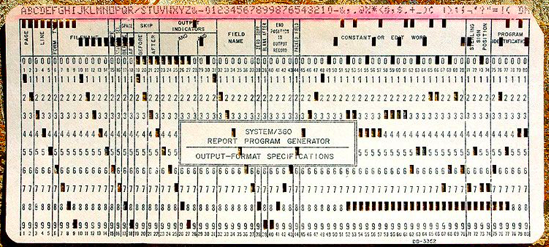

The only way we know how to program computers is by feeding them text. In the olden days, we used to program computers differently (e.g. by directly rewiring the computing machinery or by crafting punched cards – figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Programming computers by manually rewiring them.

Figure 2. Programming computers by producing punched cards.

To bring the challenge of computer programming closer to the human level of comprehension, we have collectively decided, some 70 years ago, to introduce a level of indirection and let programmers encode their intentions using pure text. Text is more intuitively accessible to humans than complicated mechanical contraptions or obtuse punched cards, so the new technology stuck.

Today, everyone programs computers by using nothing else but plain text.

What’s the problem?

Computer programs, written as plain text (i.e. source code) differ significantly from natural human languages. In what ways?

Firstly, computer source code is lexically different from natural languages. Computer programming languages are composed of severely limited vocabulary (some words used as programming language keywords, or reserved words), while other words remain free-form in order to act as unique identifiers that help name program constructs (variables, methods, modules, etc.)

Secondly, computer source code is syntactically laid out and organized differently than natural languages. Formally defined structures play much more important role in computer programming languages than they play in natural languages. Furthermore, almost all programming languages feature multiple forms of indented layouts (horizontal and vertical). Such layout is seldom, if ever, encountered in written natural languages.

Thirdly, and most importantly, there is the difference in semantics: text written in a natural language is typically understood in two simultaneous (concurrent) phases. Those phases denote:

- Text (how it is written down)

- Domain (what does the text mean)

These two phases of simultaneous comprehension are insufficient when reading a computer program (code-as-text). To understand the computer source code, we need a third dimension: execution.

To discover the operational semantics of the program’s source code, we are required to trace the source code execution.

Easier said than done. Oftentimes, opening a file containing code-as-text does not give as an easy access to grasping what is that program supposed to be doing. Unlike with natural language written down as text, where we can safely start from the top of the page/screen and follow the story as it unfolds, row by row, paragraph by paragraph, computer source code does not necessarily proceed in that fashion.

The problem therefore lies in the fact that code-as-text cannot provide us with clear understanding of how the program will behave. We can only know for sure how the program works and what does the program execute if we execute it.

Why is that a problem?

Seeing how code-as-text is an intermediary layer between human programmer and the machine that runs the program, we observe that there is an unavoidable lag between the moment when we make a change (a diff) to the source code and the moment when we learn about the impact of the change we’ve made. This lag is the crux of the problem.

In many environments, it takes a considerable amount of time between us making a diff and seeing the effects of that diff. This inevitable slowdown is negatively affecting the quality of our work.

In contrast, almost any other crafting activity is free of this annoying lag. If we’re building a cabinet, for example, the material and the tools we’re using will inform us, instantaneously, about the effects of the change we’re making. We get feedback in real time, and that feedback is ensuring that we proceed without making serious mistakes.

None such real time feedback is available in the activity of software engineering. When writing software, we work with code-as-text, which is incapable of giving us real time feedback. Once we introduce some change into the source code, we have to do a lot of acrobatics before we can see the result of that change. This is considerably slowing us down and therefore poses a serious problem when it comes to ensuring quality of our delivery.

Is there a solution?

Currently the only mainstream solution that exists for addressing the above problem is Test Driven Development (TDD). As we have seen in our TDD Dojo, when doing TDD we focus on executing our program as frequently as possible. The only way to gain insight and understanding about the effect of the changes we make to the source code is to execute the program. And because TDD is based on writing micro tests, the time lag between the moment when we make the change and the moment we execute the program and witness the effects of that change is as short as it can get.