This is a new series of posts, where we will go back to basics. We will start with the "smaller batch size" concept, which is well defined and documented in various Agile publications, such as the Scaled Agile Framework Principle #6 – Visualize and limit WIP, reduce batch sizes, and manage queue lengths.

Adopting smaller batch sizes aligns well with and complements agile principles. Small batches facilitate:

- Rapid experimentation and iteration.

- Quick feedback loops.

- Reduced development times.

- Simplicity and flexibility.

- Optimised capacity management.

Let us visualize a few example and spot these advantages.

CAUTION - I am intentionally skipping a very important and related topic, which will be covered in the follow-up blog post - Work in-Progress (WIP). Without it, leaning towards smaller batch sizes would lead to a nuclear type reaction (a process in which two particles collide, to produce one or more particles), followed by a similar meltdown.

Build a rocket

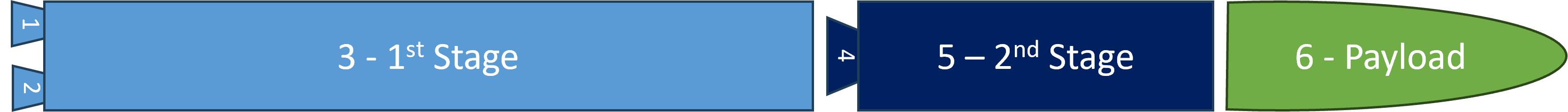

Let us construct a straightforward two-stage rocket featuring a total of three engines and a payload, represented by six (6) components. This intentionally simplified rocket design aims to maintain the clarity and simplicity of this blog post.

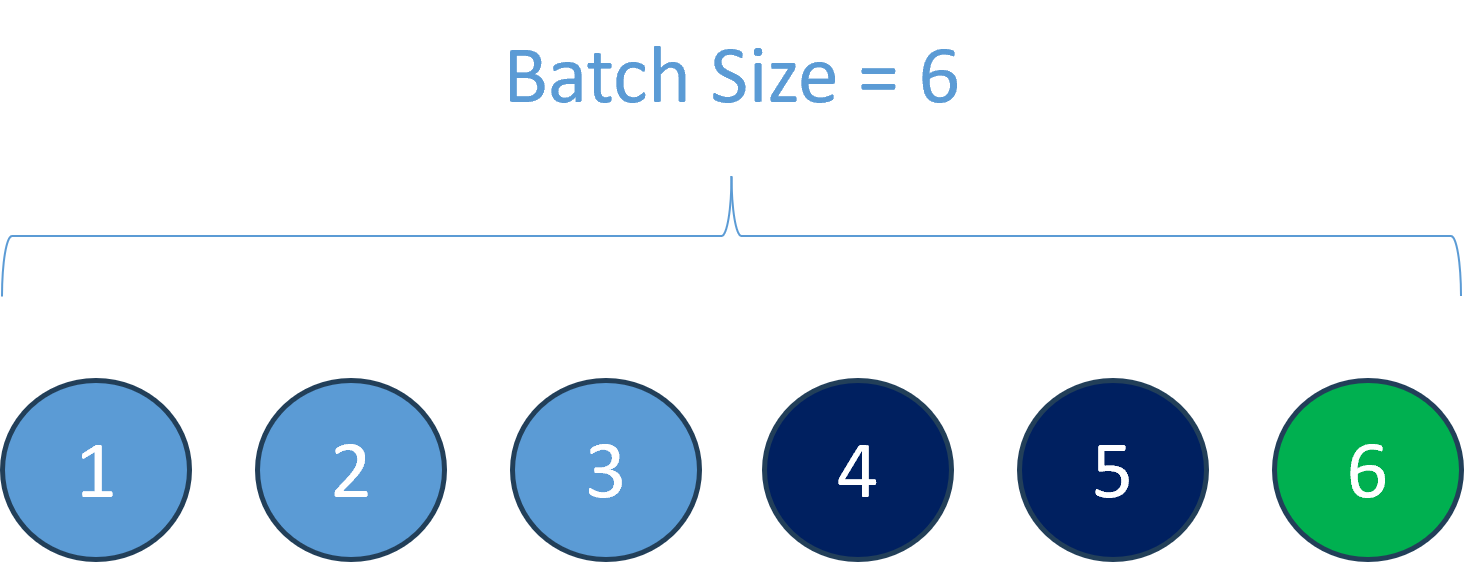

We define our batch size as six (6), indicating our intention to devour the watermelon in a single bite or, in this context, to construct the rocket in one seamless process.

This implies that all our teams commence work on the rocket simultaneously, disappear during the processing period (cycle time), and re-emerge with the finished product — the six-piece rocket. If another request for a rocket came in during the processing time, it would have to wait a very, very long time (lead time), before anyone takes note.

See The problem with big batches for another viewpoint.

Pros:

While I, like others, instinctively engage in this behavior, I struggle to identify any tangible benefits. I always get burnt!

Cons:

- Prolonged lead time: The duration required for the process to construct a rocket, spanning from the initiation of your request to the moment it stands ready on the launch pad.

- Extended cycle time: The duration required to complete one cycle to construct a rocket, from when the team of engineers starts work on the rocket to the moment it stands ready on the launch pad. Excludes placing your order and waiting for the team to be available to consider your order.

- Gradual and high risk of failures: When a rocket is shipped, and either the end-users reject it as not meeting expectations, or, worse, it malfunctions on the launch pad, the cost of failure, learning, and iterating becomes exceptionally high.

- Delayed feedback: With longer feedback loops, issues go unnoticed. See Gradual and high risk of failures.

- Reduced flexibility: Longer cycle times hinder ability to pivot quickly. Making an engine change when the rocket is ready to roll-out to the launch pad is expensive and too late.

- Complex integration: Integrating complete or near complete rockets can be challenging and error-prone, especially with Gradual and high risk of failures at the back of our mind.

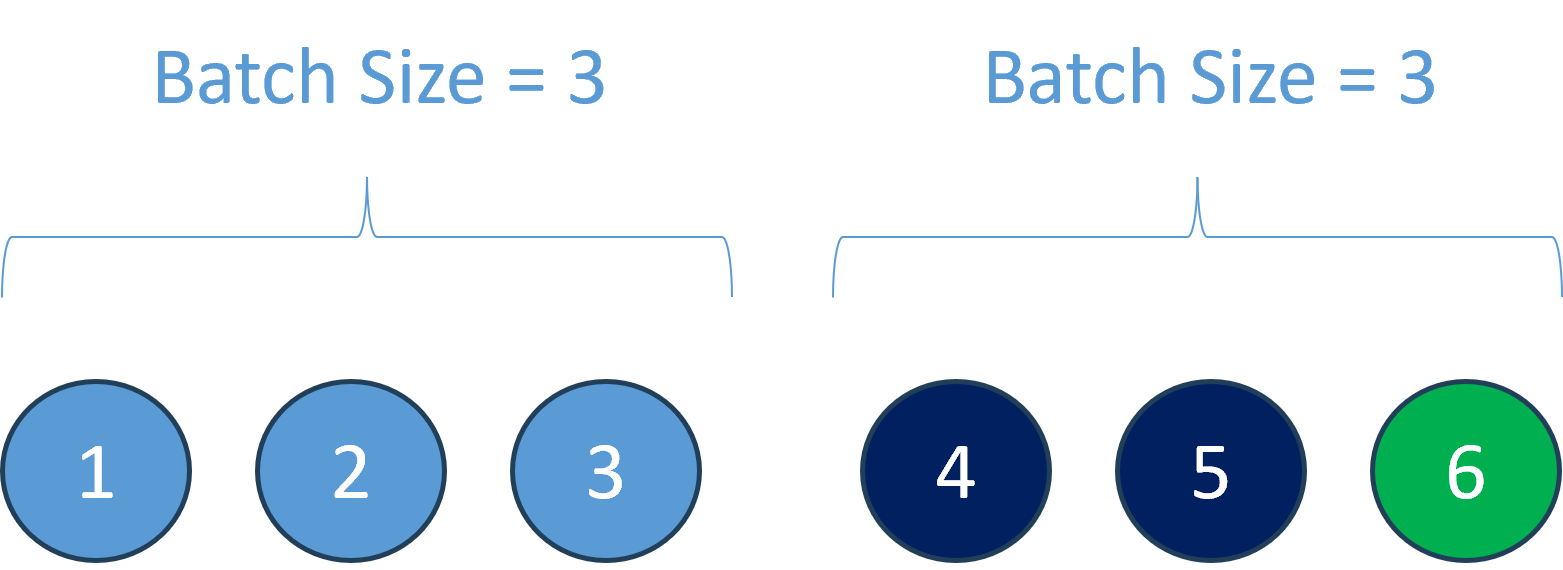

Build a rocket in two stages

By reducing the batch size to three (3), we gain the flexibility to construct the 1st and 2nd stages independently, potentially even in parallel if our capacity allows. This approach enables the team to avoid blockages, as the team responsible for the 2nd stage can proceed without waiting for the 1st stage to be completed, particularly when integration is separated from development. Rather than reiterating the drawbacks, it is evident that this adjustment enhances the drawbacks mentioned earlier. We are now observing the benefits of smaller batches, such as the ability to fail fast, pivot swiftly, and utilize idle time for innovation and improvement.

Build a rocket in small batches

By reducing the batch size to one, we see magic starting to happen. Previous cons turn into pros, such as quick feedback loops, adaptability, reduced risk, improved efficiently and dependency management, better resource utilization, continuous experimentation and improvement, and vibrant collaboration. We, for example, realise that engine (1) and (2) are identical and interchangeable, that although engines 1/2 (lower-atmosphere nozzle) and 5 (vacuum nozzle) are different, their parts are identical and interchangeable.

Dedicate some time to tuning into SpaceX's live streams from Boca Chica, and you will witness an ongoing process of experimentation, relentless improvement, and the application of small batch sizes in the construction of the Starship—the epitome of rockets.

BUT, there is a catch

As highlighted in the cautionary note, management of smaller batch sizes is important to prevent any adverse repercussions. Consider the current scenario where engines are being produced in succession. How do we effectively integrate, test, and glean insights from the rigorous hot stage tests, ensuring each stage's functionality and reliability? The challenge lies in avoiding the potential need to extensively re-engineer a substantial number of completed engines.

Our goal is to steer clear of transforming into a rigid 100% "sausage factory." Instead, we aspire to embrace an 80:20 mindset, dedicating 80% of our efforts to delivering tangible value and reserving 20% for essential activities like experimentation, continuous learning, grooming, and allowing ourselves a moment to take a deep breath. This balanced approach ensures both productivity and innovation thrive within our rocket assembly value streams.

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we delve into the significance of Work In Progress (WIP) limits.

I chose rockets because of my deep passion for space programs. I have closely followed both the Space Launch System (SLS) and SpaceX initiatives with keen interest. While both programs deliver exceptional hardware, there is a stark contrast in their approaches. One produces approximately one rocket annually at a significant cost, whereas the other achieved a remarkable feat of launching 98 rockets in 2023 — equivalent to a launch every 3.7 days. Moreover, the latter has demonstrated mastery in the realms of experimentation, rapid prototyping, and the groundbreaking concept of reusable rockets. It is important to recognize the distinct positions each program holds when considering the three simple examples above.